In a major religious liberty ruling with far‑reaching implications for American workplaces.The U.S. Supreme Court has handed down a unanimous decision in favor of a Pennsylvania postal worker, clarifying how employers must handle religious accommodation requests under federal law.

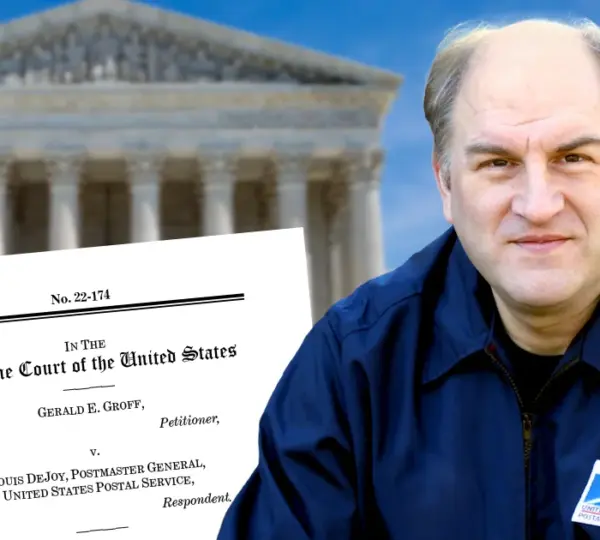

The case, known as Groff v. DeJoy, centers on whether employers can require employees to work on days that conflict with their deeply held religious beliefs — and how far companies must go to accommodate such requests under the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The Court’s decision — handed down on June 29, 2023 — was unanimous (9‑0), signaling strong agreement among justices from across the ideological spectrum on the importance of religious liberty in the workplace.

What had been a narrow dispute involving a rural mail carrier from Pennsylvania has now become one of the most important Supreme Court decisions in decades on the meaning and scope of workplace religious accommodation.The Central Question: Sunday Deliveries vs. Sabbath Observance

At issue in the case was Gerald E. Groff, a former United States Postal Service (USPS) employee from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.Groff is a devout Evangelical Christian who observes the Sabbath on Sunday — a day of worship and rest in his faith tradition.

For years, Groff’s job as a Rural Carrier Associate allowed him to avoid Sunday work without significant conflict, and the Postal Service made efforts to accommodate his religious practices.However, the situation changed after the USPS entered a contract with Amazon.com in 2013 that included Sunday package deliveries as part of the agency’s strategy to remain financially viable.As Sunday deliveries became routine, Groff found himself scheduled for Sunday shifts that conflicted with his religious observance.

Groff offered to take additional weekday or holiday work to make up for any shift he would miss because of his Sabbath, but the Postal Service ultimately disciplined him for repeatedly missing Sundays when no substitute carrier could be found After a period of disciplinary action, Groff resigned from his position in 2019 and filed a lawsuit, arguing that the Postal Service had violated Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by failing to reasonably accommodate his religious beliefs.

Title VII and the “Undue Hardship” Standard

Title VII broadly prohibits discrimination in employment based on religion — along with race, sex, and national origin — and requires employers to reasonably accommodate an employee’s religious practices unless doing so would result in an “undue hardship” on the business.For nearly 50 years, courts interpreted the phrase “undue hardship” based on a 1977 Supreme Court case, Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison. In that decision, the Court held that employers need not grant accommodations that impose “more than a de minimis cost” on the employer.Essentially, this meant that even relatively minimal burdens on the business could justify refusing a religious accommodation.

Over time, critics of the Hardison standard argued that it drastically weakened workers’ religious protections under Title VII, permitting employers to deny accommodations for even modest costs or inconveniences.Many observers, including Groff’s legal team, said the “more than de minimis” test was inconsistent with the plain language of Title VII and failed to reflect how “undue hardship” is applied in other federal contexts.Arguments Before the Court

Groff’s attorneys urged the Supreme Court to revisit the Hardison precedent and adopt a higher standard for evaluating undue hardship — one more consistent with the statutory language of Title VII and similar tests used in disability law (such as under the Americans with Disabilities Act).

They argued that employers should be required to show that granting a religious accommodation would result in “substantial increased costs” in the operation of the business before being permitted to deny it

In support of that argument, many religious organizations and civil rights groups filed briefs with the Court.

They noted that under the Hardison standard, employers could too easily justify denying religious accommodations, particularly harming workers of religious minorities whose practices might not align with standard workplace scheduling.Groups representing Muslim, Jewish, Hindu and other faith communities told the Supreme Court that the Hardison precedent forced employees to choose between their faith and their livelihood and that the standard should be clarified or overturned.

Postal worker unions, including the American Postal Workers Union, also weighed in prior to the decision, warning that special scheduling for religious accommodations could create tensions and burdens for coworkers — particularly in operations where a common day off helps with family time and community life.

The union argued that days off, especially weekends, are important for parents and families of all beliefs, not just religious adherents.

A Unanimous Ruling and a New Standard

In its opinion, the Supreme Court rejected the simplistic “de minimis” test that had guided religious accommodation cases for decades.

While the Court did not completely overturn the 1977 Hardison precedent, it clarified that mere minimal costs or minor inconveniences do not constitute an undue hardship under Title VII.

Instead, an employer that denies a religious accommodation must show that granting the accommodation would result in substantial increased costs or other significant burdens relative to the conduct of its business.

Justice Samuel Alito delivered the opinion of the Court, joined by all eight other justices — a remarkable consensus in today’s polarized legal climate.

The Court emphasized that employers must consider reasonable accommodations and cannot rely on the outdated “more than de minimis cost” formulation to justify denial.

The decision requires a deeper, more context‑sensitive analysis of whether accommodating religious practices would truly burden the business.

In clarifying the standard, the Supreme Court explained that effects on coworkers or scheduling disruptions alone do not automatically count as undue hardship unless they translate into substantial burdens on the overall operations of the employer’s business.

The decision sends the case back to lower courts to apply this clarified standard to Groff’s underlying claims.

Implications for Workers and Employers

Legal analysts have characterized the decision as a significant victory for religious liberty protections in the workplace.

By heightening the burden employers must meet to justify denying religious accommodations, the Supreme Court’s ruling gives employees greater leverage in asserting their rights under Title VII.

Experts say that the decision could have broad implications beyond Sunday scheduling — affecting how employers handle religious dress and grooming requests, observances of holy days, and other workplace practices tied to faith.

It is expected to influence litigation, human resources policies, and employer‑employee negotiations for years to come.

The decision has been welcomed not only by Christian groups but also by organizations representing a wide range of faith traditions, who see it as a corrective to decades of lower‑court decisions that too liberally interpreted Hardison in favor of employers.

Many minority religious communities in particular have noted that under the old standard, accommodations were often denied because the religious practices at issue were unfamiliar or less common.

What Happened to Groff?

As part of the lower‑court record, it’s worth noting that Groff’s original lawsuit arose after he was disciplined for missing more than two dozen Sunday shifts because of his Sabbath observance.

Those refusals occurred after his USPS office began Sunday deliveries as part of the Amazon contract, and after efforts to find volunteers to cover his shifts often failed.

Eventually, facing disciplinary action, Groff resigned his position.

The Third Circuit Court of Appeals had upheld the USPS’s actions under the old “de minimis” test, finding that exemptions from Sunday work would impose undue hardship by burdening coworkers and disrupting operations.

That ruling was reversed and remanded by the Supreme Court in light of the clarified undue hardship standard.

The Supreme Court’s decision does not automatically entitle Groff to a specific accommodation, but it opens the door for his claim to be reconsidered under the correct legal standard that properly reflects Title VII’s protections.

A Broader Legal and Social Context

The Groff v. DeJoy decision fits within a broader trend of the Supreme Court affirming religious liberties in the workplace and public life.

In recent years, the Court has considered and ruled on multiple cases involving conflicts between civil rights laws and religious practices, routinely emphasizing the need to protect individuals’ ability to practice deeply held beliefs without undue interference.

While the decision strengthened employees’ rights to religious accommodation, it also underscored that employers still retain legitimate interests in maintaining workplace operations.

The Supreme Court’s clarified standard — focused on whether an accommodation imposes a substantial burden on the overall business — is designed to strike a balance between those interests and employees’ constitutional and statutory rights.

Looking Ahead: Employer Policies and Legal Challenges

Following the decision, workplace legal experts have urged employers to revisit and revise their policies around religious accommodation requests.

Human resources departments are encouraged to establish clear procedures, encourage open dialogue with employees, and proactively identify potential accommodation solutions before conflicts escalate to litigation.

At the same time, some analysts predict that clarifying the undue hardship standard may lead to more claims as employees become empowered to bring accommodation requests under Title VII — particularly when they believe their practices have previously been overlooked or dismissed under the old de minimis test.

Conclusion: A Landmark Win for Workplace Religious Rights

The Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling in Groff v. DeJoy represents a significant reaffirmation of religious freedom in American workplaces.

By clarifying how Title VII’s “undue hardship” standard should be applied, the Court has strengthened protections for workers whose sincerely held religious beliefs require accommodations that conflict with standard job requirements.

While the case began with the personal story of one mail carrier in Pennsylvania, its implications now reach across the nation — touching faith communities, employers, legal professionals, and ordinary workers alike.

At its core, the decision reaffirms a fundamental principle of American law: that employees should not be forced to choose between their deeply held religious convictions and their livelihoods.